-

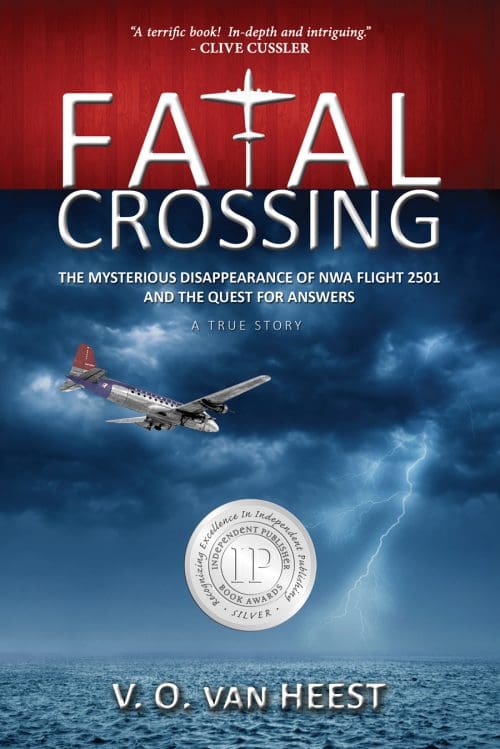

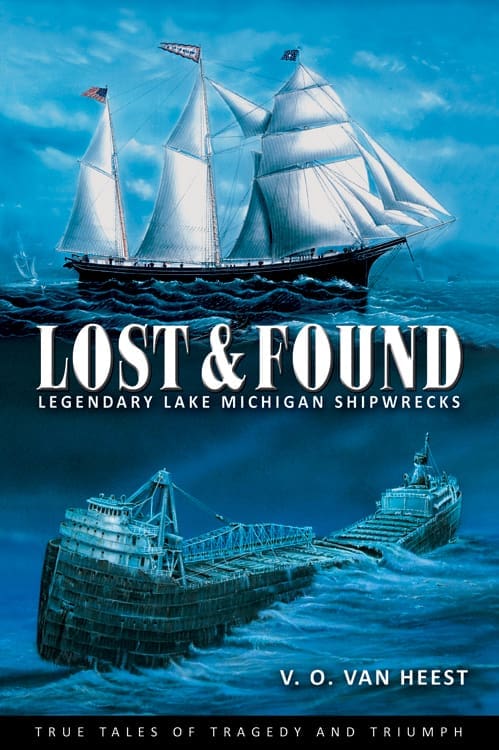

Legendary Lake Michigan Shipwrecks

True Tales of Tragedy and TriumphTitanic sank in 1912 and the stories of amazing survival and tragic loss made the ocean liner famous. Titanic’s discovery in 1985—and the images captured of the grand staircase, the pilothouse, and the dripping rusticles—made Titanic legendary.

Likewise, the many shipwrecks presented in Lost and Found became even more famous after their discoveries than at the time of their losses, gaining notoriety as historic attractions, archaeological sites, and in some cases, over bold salvage attempts or precedent- setting legal battles. Through riveting narrative, the award-winning author and explorer takes the readers back in time to experience the careers and tragic sinkings of these ships, then beneath the lake to participate in the triumphant discovery and exciting exploration of their remains and the circumstances that led to their status as legendary shipwrecks.

The vessels in this comprehensive publication span the age of sail, steam, and diesel on the Great Lakes from the earliest schooners to the sidewheel steamers, propellers, carferries, self-unloaders, and yachts. They include ships lost in Wisconsin, Illinois, Indiana, and Michigan waters that were discovered by some of the lake’s most prolific wreck hunters, including the author’s own organization—Michigan Shipwreck Research Associates—in partnerships with legendary wreck hunters David Trotter, Ralph Wilbanks, and nationally acclaimed author Clive Cussler. Presented chronologically based on the date discovered, these shipwrecks provide an overview of evolving diver attitudes and conduct, as well as the laws affecting exploration and documentation.

-

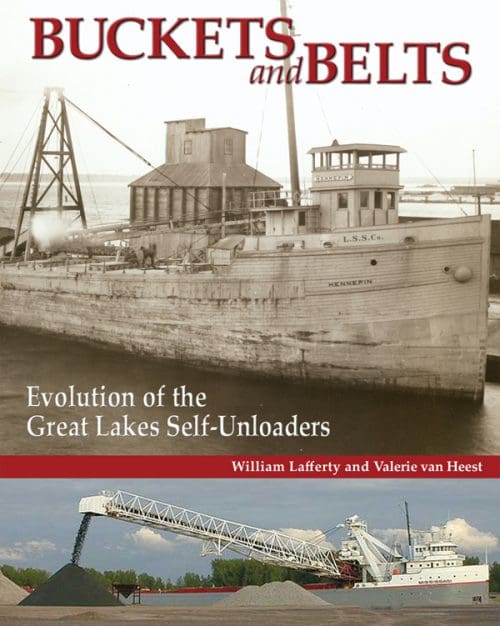

Evolution of the Great Lakes Self-Unloaders

A Must-Read for Boatnerds and Shipwreck Enthusiasts On a warm summer afternoon in 1927 off South Haven, Michigan, an old barge began taking on water. Helpless to staunch the flow and realizing their vessel would inevitably sink, the crew escaped to the accompanying tug, and watched as their ship plunged beneath Lake Michigan. Its loss unlamented, its career unheralded, it slumbered on the sandy bottom in the same obscurity that had shrouded its earlier work days as a steam freighter sailing the Great Lakes. However, the vessel’s anonymity ended in 2006 when Michigan Shipwreck Research Associates located the sunken wreck of the Hennepin. It is now listed on the National Register of Historic Places as the world’s first self-unloading vessel. Buckets and Belts: Evolution of the Great Lakes Self-Unloader traces more than a century of innovative technological advancements in the conveying of bulk cargos from the Hennepin’s conversion to a self-unloader in 1902 to today’s mammoth thousand-foot long lakers. Enhanced with the most comprehensive collection of self-unloader images ever published and dozens of underwater photographs, the book also explores the lives of the people who designed these vessels, the crewmen who sailed them and the self-unloaders that tragically went to the bottom, often taking entire crews with them. -

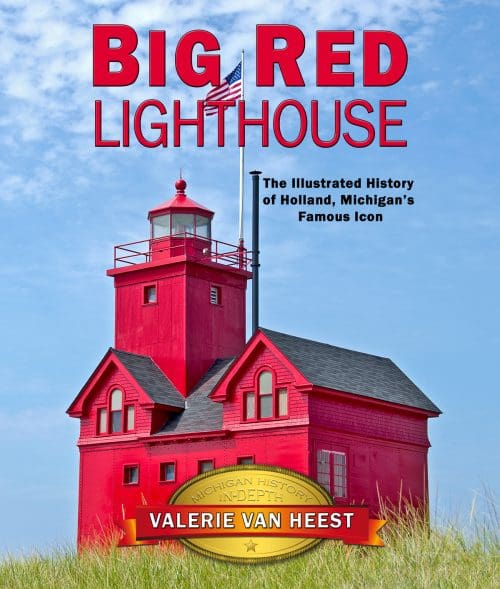

Holland Harbor's South Pierhead Lighthouse, known as BIG RED, was not always BIG, not always RED, and not always a LIGHTHOUSE.

The fascinating and misunderstood history of Holland's navigational aid began when the United States Lighthouse Board erected a small beacon light at Holland in the 1870 after visionary Dutch settlers spearheaded the development of a navigable channel- one that connected their new colony on the shores of Black Lake with Lake Michigan, the Great Lakes, and beyond. That first light and three navigational aids built as improvements over the next 66 years played critical roles in safely guiding mariners along Michigan's treacherous coast and into Holland's harbor, allowing the town to develop first into a busy commercial port and later into a tourist destination. In time, the lighthouse became an endearing cultural icon, however, technical advances in navigation rendered it obsolete and facing possible demolition. In the 1970s a new generation of visionary Hollanders formed the Holland Harbor Lighthouse Commission to preserve the structure, which they affectionately branded "Big Red." Their efforts led to its listing on the National Register of Historic Places and secured its future. Big Red still stands sentinel at the channel mouth. It can be seen from Holland State Park, which is visited by some two million people per year. However, unlike any other Michigan lighthouse, this iconic structure is surrounded by privately owned land, which impedes public access. This book explains how that came to be and provides written and visual access to one of Michigan's most photographed and recognizable lighthouses.