-

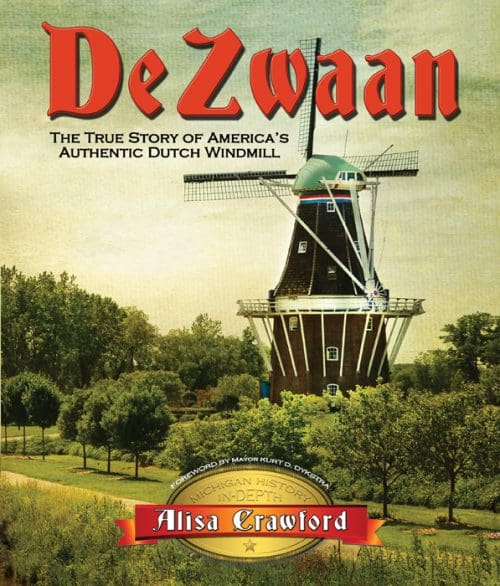

The True Story of America’s Authentic Dutch Windmill

America's only authentic operational Dutch windmill, De Zwaan serves as Holland, Michigan's iconic connection to the community's roots. Believed to have been built in 1761, then moved to the village of Vinkel in North Brabant, the Netherlands, where it produced flour for eighty years, the windmill was dismantled, shipped to the United States, and reassembled in 1964. For more than a half-century, "The Swan" (the translation of De Zwaan) has drawn visitors from all over the world. Alisa Crawford, De Zwaan's miller- and the only Dutch certified miller in the United States- shares a fascinating look at the story of this historic structure as well as other American- and Dutch-built windmills. Through years of research and interviews with people connected to De Zwaan, she reveals the true origins of its construction, the damage it sustained in World War II, its journey to America, its resurrection as a working mill, its rise as a premier Midwestern attraction, and even the effect its relocation had on the village of Vinkel. Delivering the only complete story of this working mill and an extraordinary collection of images spanning its life in the Netherlands and America, this book is a collector edition to commemorate De Zwaan’s productive and lengthy career and the City of Holland’s commitment to this significant monument of living history. -

Out of stock

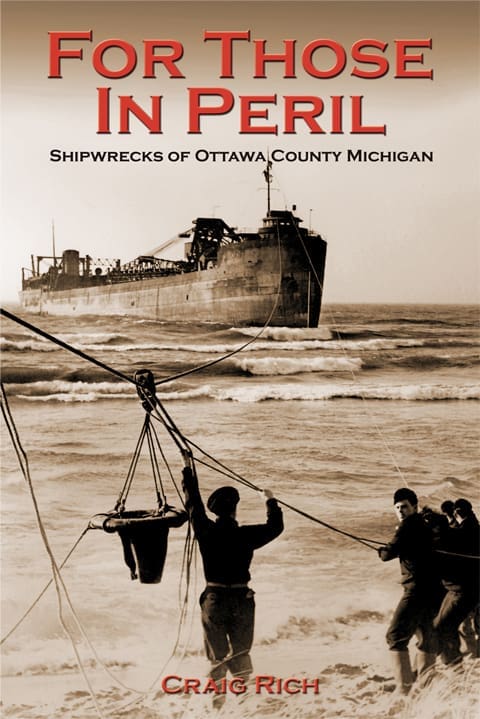

Shipwrecks of Ottawa County Michigan

The lyrics of the hymn Eternal Father Strong to Save pay homage to sailors who risk their lives in the course of everyday work and aptly express the intriguing maritime heritage of Ottawa County, Michigan, a region along the eastern shore of Lake Michigan that saw many a ship and sailor lost. The lakeshore communities of Grand Haven and Holland became thriving commercial ports in the latter half of the 19th century and bore witness to the evolutionary changes in Great Lakes transportation. Early wooden sailing vessels were replaced by wooden steamers, which soon made way for steel vessels, which grew to include today’s “thousand footers.” Schooners laden with lumber and stone gave way to luxury passenger steamships ferrying Chicago’s wealthy tourists to Ottawa County’s grand tourist hotels. Families were changed forever when husbands and sons were lost to the gales of November, and fortunes were lost when vessel owners tried to get just one more trip in before the harsh winters closed the ports. Many of these vessels were simply overtaken by age, mechanical failure or shifting sands. Some broke up on shore while others were refloated to sail again. Some were left to rot at the dock while others simply sailed over the horizon into oblivion never to be seen again. Many now serve as “ice water museums,” attracting scuba divers, explorers and historians to these shipwrecks that comprise an important part of the early history of Ottawa County and the Great Lakes region as well. -

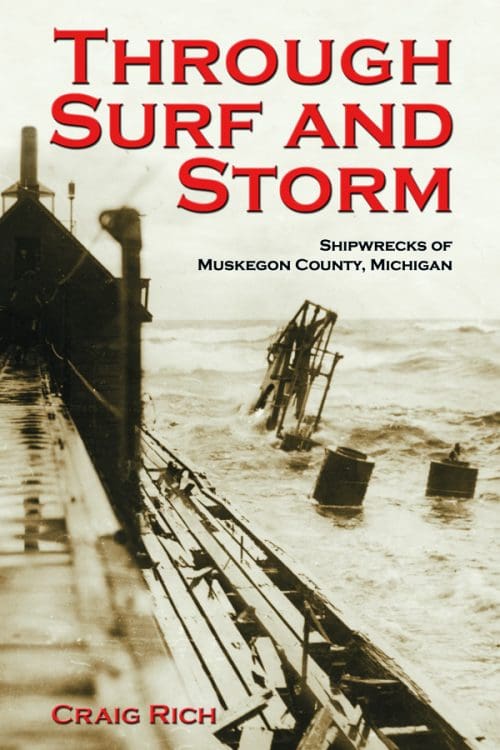

Shipwrecks of Muskegon County Michigan

"We're always ready for the call, We place our trust in Thee. Through surf and storm and howling gale, High shall our purpose be." The words of the United States Coast Guard hymn bring to mind the dedication of those who always have been prepared to risk their own lives to save those whose lives are in peril on the Great Lakes. Whether the U.S. Life Saving Service, the U.S. Coast Guard or, at times, Keepers of the U.S. Lighthouse Service, mariners on the Great Lakes knew there were good men and women dedicated to coming to their assistance in times of emergency. As Michigan’s premiere lumbering port during the 19th century, Muskegon served as the eastern terminus for a huge fleet of scows, schooners, side-wheelers, steamers, and propellers for the past 180 years. From humble beginning in the 1830s until the lumber trade was replaced by stone, aggregate, and other commodities in the early 20th century, the ports of Muskegon and White Lake—and to a lesser extent Duck Lake and Mona Lake—saw dozens of vessel arriving and departing daily. And often, those departing never arrived at their destinations; and those expected never made port. Fierce Lake Michigan gales, sudden snow squalls, waterspouts, and even a rarely recorded Lake Michigan tidal wave, or seiche, capsized vessels, stranded them on shore, froze their rigging, tore their sails, and tossed their crews into the icy cold water. Small schooners carrying lumber eventually gave way to huge car ferries transporting railroad cars full of packaged goods across the lake to points west, as well as luxurious passengers steamers bearing businessmen and families to and from Chicago, Milwaukee, and other Great Lakes port cities. While vessel capacity and comfort were increased, the size of the losses were as well. Many of these vessels sank in deep water while others washed ashore to be broken up by wind, waves, and ice. Some exploded or burned at the dock while others simply rotted away after plying the lakes for decades. Modern man may catch glimpses of these historic vessels as shifting sands uncover and recover beach wrecks or the bones of abandoned schooners in shallow waters. Scuba divers visit other wrecks—many in surprisingly good condition—while the search continues for dozens of others still hidden under fathoms of cold, dark water.