The Holland Harbor Light and Fog Signal Building

United States Lighthouse Service

During the Andrew Jackson administration in 1830, responsibility for the lighthouses was transferred to the Treasury Department. The lighthouses fell into disrepair over the next 20 years, until 1852 when Congress (during the administration of Millard Fillmore) acted to create an autonomous Lighthouse Board which divided the U.S.A. into 12 districts. Lake Michigan became part of the 12th Lighthouse District.

Evolution of the Holland Lighthouse: This sketch by Dan Aument shows the first lighthouse which was put into operation in 1870 (beware that many accounts incorrectly note that it was installed in 1872).

1870 Wooden Light tower: Since 1847, Dr. Albertus Van Raalte had started what would become a long and tedious process to see that the connection between Lake Michigan and Black Lake to improve the Holland harbor to allow for shipping and build a lighthouse for safety. His efforts led to the construction of the first lighthouse tower on the south pier head in 1872 after the U.S. Congress, with influence from Michigan’s Senator Ferry, appropriated $4,000.

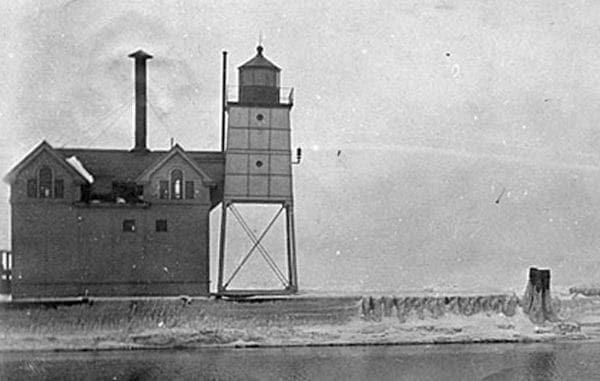

A rare photograph of the 1870 light. The light was about 30 feet above lake level and contained a fifth order harbor light. The light tower structure was accessed by an elevated wooden catwalk which ran the length of the pier which extended straight out into Lake Michigan. Below the ten-sided glassed in lantern room was a small lamp workroom, where the lamps, fuel and accessories necessary for maintaining the light were stored. There the lamps were cleaned, refueled, serviced, and stored when not in service. The lighthouse keeper had to carry his lighted oil lamp along a catwalk, which extended from the watchtower on the shore out to the small completely enclosed lamp room in the lighthouse. Then he climbed the interior ladder up to the ten-sided glass lantern room and lit the kerosene lamp inside the magnifying lens. When fog obscured the light, he signaled incoming boats by blowing an 18 inch fish horn often used on sailboats.

1901 Freestanding steel tower: By the early 20th Century both the pier and the wooden lighthouse had taken a beating from the weather over the years. In 1901, when the harbor was finally finished, a breakwater was built and the wooden tower was replaced by a taller, steel structure which housed the lamp.

This photo looks WNW past the formidable looking base of the steel tower toward the end of the north pier head. Note the wooden deck of the pier head. The steel tower was an obvious improvement; not only could it better withstand severe weather, but, by raising the height of the light, it could be spotted by incoming vessels as far away as thirteen miles. The fish horn, however, was found insufficient to serve as a warning during fog. This August 1906 photo shows the heavy wooden timbers of the pier and the elevated wooden catwalk leading to the steel tower.

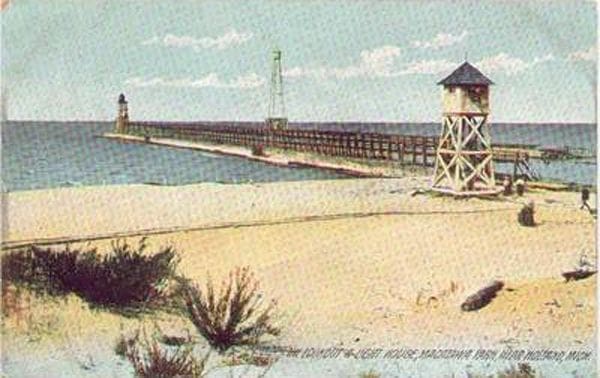

This pre-1907 view of the south pier shows (from left to right) the steel tower, the tall range light (colored green in this hand tinted photo), and the watch tower in which the lighthouse keeper and his assistants stood watch in six hour shifts.

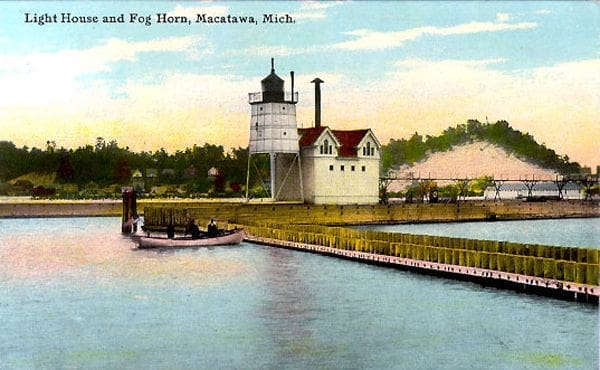

1907 Steel Tower and Fog Signal Building: In 1907 the 12th Lighthouse District, which had federal jurisdiction over the lighthouse, designed and constructed a separate building, the basis of today’s lighthouse, to serve as a fog signal building. This Queen Anne Victorian structure, unlike its two predecessors, was not placed on legs, thereby affording greater stability. It contained a steam-operated fog signal operated by two coal fed Marine boilers, which produced steam to sound the locomotive whistle used as a fog signal. This view of south pier after 1907 shows reconstruction of elevated wooden walkway, rear range light (in foreground) and fog signal building with free standing steel tower housing the head light. Although this is a “hand tinted” card, the pale yellow over deep maroon coloration on the fog signal building accurately represents the original color scheme for a number of years. The Light Tower was later moved to Calumet. In this 1912 view to the south, the ten inch tall locomotive whistle may be seen sticking out of the right (west) side of the steel tower.

In this view to the north east with Mt. Pisgah at right rear, note that the heavy wooden catwalk has been replaced with one made of steel.

1934 Electrification: In 1934 the light was electrified and moved atop the fog signal building, and the Fresnel lens transferred to the Holland Museum. Then in 1936, plans were made to abandon the steam driven fog signal, nearly 30 years old, and install air powered horns using electricity as a power source for air compressors. Electrification marked the end of the era of lighthouse keepers that had spanned 68 years. Soon thereafter in 1940 the Lighthouse Bureau was abolished in a cost-cutting measure enacted by President Franklin D. Roosevelt, and the U.S. Coast Guard became responsible for the lighthouses.

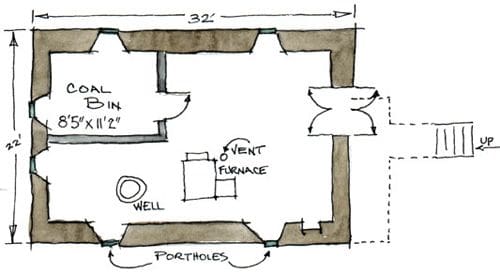

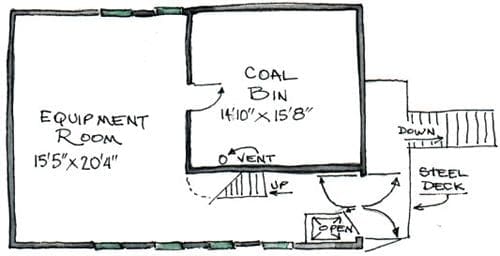

The Crawl Space as it was laid out after 1936 when the building furnace, six round portholes and a proper exterior door were added. The basement, as it was called after 1936, was above the level of the pier head.

By climbing about ten feet up the steel steps on the east side of the building, one gains access to the First Floor of the lighthouse. Stepping inside, one can either climb the steps to the upper floors, or walk ahead into the equipment room. There are two small windows (tinted green in the above drawing) in the north wall and four windows in the south wall.

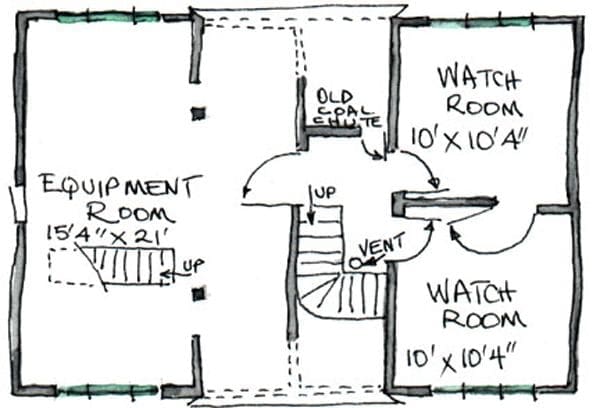

This floor plan shows the second floor after the removal of the steam boilers in 1936. The windows in the two watch rooms allowed the lighthouse keeper to look north and south. For a clear view west, one had to climb two flights of steps to the lantern room at the top of the lighthouse.

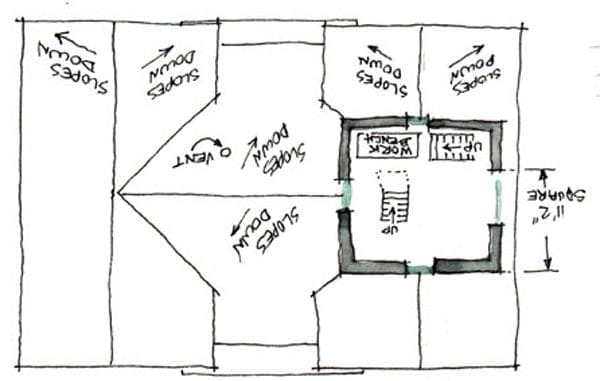

The Tower Floor lamp room is roughly centered above the gables on the west end of the building.

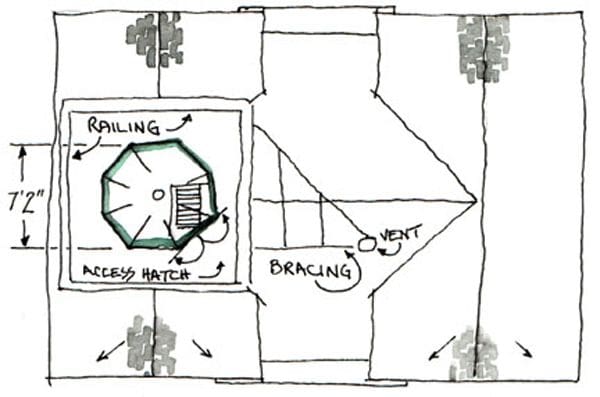

The Lantern Floor, the top most level of the lighthouse, consists of the 10-sided lamp enclosure. Below the glass on the southeast side is an access hatch to the small deck about 45 feet above the surface of Lake Michigan.

In this late 1940s view, the color scheme of the lighthouse appears to be white on the bottom and red for the light tower.

Coast Guard Jurisdiction: In 1956, the Coast Guard sandblasted the tower and painted it bright red to satisfy a requirement for the aids to navigation that a structure or light on the right side of any harbor entrance must be red.

In 1971 the lighthouse was declared to be surplus since the Coast Guard could not justify the expense of repair and maintenance of this structure that no longer housed the electrically operated light and fog horn. Private citizens started a petition and letter writing campaign to save the lighthouse. In 1974 the Holland Harbor Lighthouse Historical Commission was formally organized to coordinate the effort.

Holland Harbor Lighthouse Historical Commission: In 1978 the Coast Guard transferred ownership to the commission and, with it, the responsibility for the preservation of the lighthouse. Repairs and maintenance of the lighthouse are paid for out of endowment funds raised by the commission. Twice a year, the Coast Guard inspects the facility and maintains the light. A new $6,000 light that can be seen for 20 miles has been installed. The use of a fog signal had been discontinued. The original Fresnel lens is on display in the Holland Museum. In 2007, the United States Department of the Interior announced that the Holland Harbor Light would be protected, making it the 12th Michigan lighthouse to have such status.

Lighthouse keepers: The Holland Lighthouse was “home” to two assistant lighthouse keepers, needed to operate the fog signal equipment. At about the same time that the original wooden tower was built in 1870, a two story residence was erected a couple hundred yards due east of the lighthouse where the chief lighthouse keeper resided.

The first Holland Lighthouse keeper was Melgert Van Regenmorter who served from December, 1870 to April, 1908 receiving an annual salary of $540. Because the residence and the lighthouse itself were government property, they were expected to be maintained in orderly and nearly spotless condition: no dust allowed anywhere in either building, and the brass equipment to be highly polished. The Lighthouse Bureau believed that slovenly building and equipment conditions would lead to apathy about maintenance of the all-important light itself.

In 1901, during Van Regenmorter’s tenure, the freestanding steel tower replaced the wooden structure, and then six years later, in 1907, the steel fog signal building was built behind the steel tower which utilized steam-driven equipment to operate. Because Van Regenmorter knew nothing about steam power and was not eager to learn, he retired and lived the remainder of his life in Macatawa. Charles Bavry took over as keeper in April 1908 and served until December, 1910 at an annual salary of $650. George Cornell served two months from December, 1910 to January, 1911. Edward Mallette replaced Mr. Cornell and served until February, 1912.

Joseph M. Boshka entered the Lighthouse Service in 1897 and he served at Holland beginning in 1912. The lighthouse was tended during the times of year that the waters were navigable with the keeper and his assistant standing six-hour shifts. Boshka reportedly had a keen ability to detect the onset of fog. This was a particularly valuable skill as it took 45 minutes to develop enough steam to operate the fog signal. Boshka served until 1940 when the Coast Guard took over service of light houses, and retired to live in Macatawa.

The deserted lighthouse keeper’s residence caught the eye of artist Miriam Kesterson in 1963, just three years before it was demolished as part of President Johnson’s “Beautify America” program.